Alternatives to My Normal

Photo/Jonathan Dimes.

By Iandry Randriamandroso

I am a community artist, a muralist, graphic artist, and an educator. For this piece, I wanted to reflect on how my work has been transformed by the pandemic. Like everyone else, the COVID-19 pandemic impacted my life as an individual but mostly the way I do my work. It has transformed how I deliver my drawing classes at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas (UNLV), how I make a mural, and how to implement community mural-making projects.

Remote Drawing Classes at UNLV (Department of Art)

In addition to my life in general, the COVID-19 pandemic forced me to change my drawing classes at UNLV dramatically after the spring break in March 2020. COVID-19 was plaguing the world population, including the United States, and school was closed for any in-person classes. All of a sudden, I had to deliver drawing classes remotely in the middle of the semester. I wiped out the existing plan in the syllabus and had to revise it quickly to fit into the new remote class format. Though UNLV and Department of Art leadership tried their best to help the UNLV community to cope with the situation, as an instructor, I felt like I was a frontline worker.

At the beginning of the semester, I made sure that my students understood their responsibilities to succeed in my classes. One of those was to focus on being familiar with Canvas, a web-based learning management system that UNLV provides to help instructors and students access and manage course-related materials, and to communicate online. During the first month of the semester, I asked every student to be well-versed in using it for my classes. So when we had to make the sudden class format change, I decided to use Canvas as the main tool for remote classes since it was available for everyone and familiar to everyone. The trust I built with my students during the earlier part of the semester was very helpful to get through these unexpected changes together.

The first thing I had to transform for my classes was how to give class instructions. With in-person classes, I could just give them verbally at the beginning of the classes. But for remote classes, I had to write down every detail of instructions in advance so students could read them at the beginning of the classes. Naturally, it required more class preparation time on my side to generate easy to follow class instructions for each class. But that was the easy part.

The next thing I had to transform was the items/subjects to draw during the classes. In-person classes, we could just use the existing drawing props in studios. But, when everyone was at home, we couldn’t use them anymore. Limited art supplies students had at home were also an issue. I had to choose something available at home to be used as subjects to teach a particular drawing skill per the curriculum. I think we went through almost all possible items in bedrooms and kitchens. With limited subjects to choose from, creating interesting drawing projects for classes was not easy and demanded lots of creativity and imagination from me. However, with cooperation and trust from the students, we could manage the second half of the semester quite interestingly. My favorite was a storytelling drawing project and a drawing worth gifting, which produced some interesting and personal artworks from my students.

Among many aspects of art classes, the most challenging part to transform was how to do the critique in the class. In normal times, I would walk around the class to observe my students’ artworks and give them advice on the spot. Corrections were made instantly and at the end of class, we would take 15 minutes for everyone to share whatever they had done that day. Unfortunately, when the class format was changed in March 2020, not everyone had an adequate tool to share their screens. And the critique was critical for the class, we could not skip it. So, we decided to use the Discussion function of Canvas. Each day, at the end of our remote classes, I asked students to upload their drawings in a discussion tab and everyone in the class was able to give praises and advice to each other’s drawings. I also wrote my critiques and how they could improve them there. It involved lots of photos and many written comments in each class. Thankfully, my students were active during the class critiques, and we could achieve the goal of the class critique, learning from each other’s comments.

Though Canvas was not designed for remote art class delivery but with constant evaluations and my students’ participation, we all succeeded in the end. This does not mean that we did not have issues along the way. We resolved them as best as we could and the semester ended well. This was my first pandemic-transformed work experience, and it prepared me for my next mural projects in the summer and remote drawing classes in the 2020 fall semester.

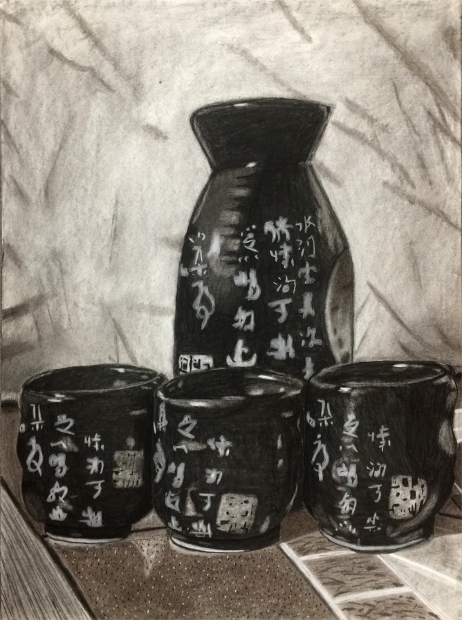

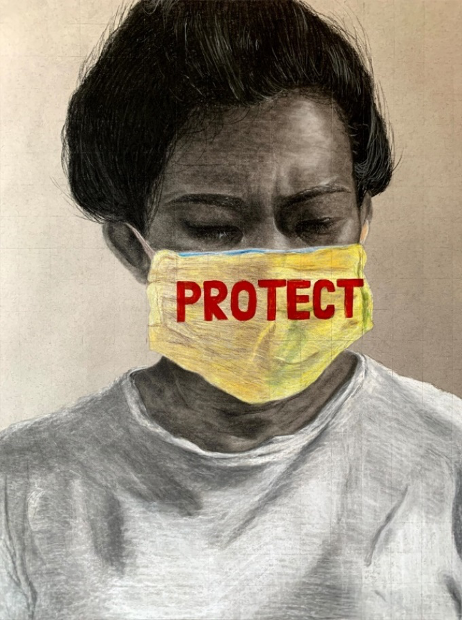

Two artworks my students at UNLV, Department of Art produced during the remote drawing classes in Spring 2020 semester. From left to right: A Charcoal Drawing by Michael McDougall and a Mixed Media Drawing by Ariana Rafael.

The Remote Mural Project Produced by Jubilee Arts

After my spring semester at UNLV ended, I had an opportunity to travel to Baltimore to implement a remote mural project with 10 youth who were participating in the Art@Work program, a five-week mural artist apprenticeship program produced by the Baltimore Office of Promotion and the Arts and Jubilee Arts in Baltimore. Since its inception in 2015, I have participated in the Art@Work program every summer as a lead artist and taught local youth to produce murals as public art in their communities. This year, the same program produced a quite different experience because of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Photos of myself painting 2 artworks to be a part of the Art@Work mural Together Apart. Photos/Keneth C. Clemons

In normal times, the program starts with a one-week training for lead artists and to develop art activities for the five-week program. This year, the usual one-week training was replaced by weekly Zoom meetings for a month. I enjoyed it because it allowed me plenty of time to prepare for the project and helped the team with building relationships and preparing for potential issues that could arise during the five-week program.

Our team was tasked to create artworks that would beautify the lobby, waiting area of the pediatric clinic, and 10 exam rooms in the Total Health Care Pediatric Clinic in Baltimore. Since this was a remote mural-making project, the first thing I did was to make sure my youth participants understood that this was still a job even though they were at home, not at a mural site.

Even though our task was to create multiple artworks for multiple locations, my team and I wanted to have one mural divided into multiple pieces which could also serve as an independent artwork individually. To accomplish that, we adopted the concept of a quilt for our mural. Each youth was given a 36” x 36” wood panel and painting kits to create their pieces. We had a Zoom meeting every working day, and I checked the progress of each youth’s work every day.

The program includes three phases: the first phase is community engagement, the second phase is design development, and the third phase is implementation. From the first phase planning, we had to transform the process significantly due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Normally, for the first phase, youth would go out in their neighborhood, knock on doors and walk down the streets to interview community members and get their input for community murals. Unfortunately, that was not an option this time. Instead, we had to use Zoom and youth were all in their homes and could interview only a limited number of invited community members.

Similarly, for the second phase of design development, the youth had to design their ideas at home and share their screens through Zoom to discuss and decide on what the community mural would look like. In normal times, when we completed designing the mural, the program would usually invite community members to gather for an event where the youth presented their designs to the community to get their approval. This summer, we could gather together only online through Zoom with a limited number of participants.

For the third phase, which was mural implementation, in past summers I was able to interact with youth at the mural sites and could see their mistakes instantly and correct them right away. But for this year, we were all in different places, and there were inevitable delays to notice mistakes and make necessary corrections. To mitigate the delays, I tried to give detailed demonstrations of techniques via Zoom at every step so the youth could apply them in their works with fewer mistakes.

It can be always a challenge to work with youth. But this was a different kind of challenge—to create a quality mural with artwork pieces that were generated by 10 youth at their homes with only online interactions. However, it was not impossible. It is a metaphor for the time we are living in now. We created individual pieces but when we put them together, we could create one mural Together Apart. In total, we painted 16 pieces, creating one mural like a quilt.

Three members of my Art@Work team posing with their completed artworks. Photos/Nate Larson.

Mural for Creative City Charter School

Another project I had a chance to work on this summer was creating a mural for Creative City Charter School in Baltimore. In general, murals transform physical spaces. Surely, the mural painted on the front wall of the Creative City Charter School this summer achieved that. However, due to the COVID-19 pandemic, the way to implement a community mural project was also transformed.

Photo/Iandry Randriamandroso.

To implement a mural, I usually hire assistants to paint the mural with me. That part was the same for this mural. However, how to interact with them at the site changed for COVID-19. We all wore masks and stayed at least six feet apart from each other at all times. We disinfected all common surfaces we touched to make sure of our safety. The COVID-19 pandemic, unexpectedly, helped me to be more organized in setting up mural materials and putting my assistants to work. In the past, my assistants moved freely to work on any parts of the mural and used any materials they needed. But this time, I had to organize the workflows and access to materials in advance to minimize contacts among us.

Having a community painting event is a common practice of my community mural projects. This project was not an exception. Though a community event always requires lots of preparation at any time, having a community event during this COVID-19 pandemic was a whole different game because we had to do it while practicing social distancing. To prepare it, I worked with the staff of the Creative City Charter School to create a safety plan, and we implemented all necessary safety measures. We divided the mural into eight sections with a distance of at least six feet and only one individual or one family responsible to paint one section of the wall at the same time. All participants were required to keep their distances at least six feet from each other and masks and gloves were provided and mandatory during the event. All art supplies were separated, organized, and disinfected with alcohol after each use. Implementing a community mural project during a pandemic was more challenging and required more planning but it was not impossible at all.

The COVID-19 pandemic is still ongoing and has devastated lots of people. Through these activities, I realized that we could adapt and transform our behaviors to make things happen even during the pandemic. To me the most transformative is the reaffirmation of my belief that a common goal can be achieved by people's willingness to trust, respect, cooperate, and work together. This was true to all of those three art activities that I have shared here, but as a society, we still need a lot of work to arrive at a common goal during this pandemic.

Community painting day at the Creative City Charter School. Photos/Iandry Randriamandroso.

Photo/Olga Townsend.

Iandry Randriamandroso is a community artist, muralist, graphic artist, and educator. He specializes in visual and mixed media art-making that focuses on environmental and social subjects. He received a B.F.A. from St. John’s University and an M.A. in Community Arts from the Maryland Institute College of Art. His goal is to create art that is inclusive and accessible to everyone. He uses his artworks as educational tools to facilitate inclusive and hands-on presentations, community arts workshops, art classes, and mural projects in public and private venues.

Learn more about his work on Iandry’s website B’more Birds and find him on Instagram.

Thank you for visiting Humanities Heart to Heart, a program of Nevada Humanities. Any views or opinions represented in posts or content on the Humanities Heart to Heart webpage are personal and belong solely to the author or contributor and do not represent those of Nevada Humanities, its staff, or any donor, partner, or affiliated organization, unless explicitly stated. At no time are these posts understood to promote particular political, religious, or ideological points of view; advocate for a particular program or social or political action; or support specific public policies or legislation on behalf of Nevada Humanities, its staff, any donor, partner, or affiliated organization. Omissions, errors, or mistakes are entirely unintentional. Nevada Humanities makes no representations as to the accuracy or completeness of any information on these posts or found by following any link embedded in these posts. Nevada Humanities reserves the right to alter, update, or remove content on the Humanities Heart to Heart webpage at any time.