Self-Discovery

By Ted Hartwell

The COVID-19 pandemic has brought with it not only the risk of contracting a potentially deadly illness, but the measures necessary to mitigate its spread have themselves been catalysts for a whole range of mental health disorders, including addictive disorders. Many have experienced personal loss (of loved ones, relationships, financial security), isolation from family members and friends, and the boredom that comes with having too much time on your hands being stuck in one place. These are all potential risk factors for addictive disorders, whether one is already in the firm grip, on the edge, or somewhere in one’s recovery journey. One of those addictions can be as hidden as the virus that has plagued us for the past year and a half, and sometimes as deadly.

The great majority of people who choose to gamble can do so for fun and entertainment, without suffering any long-term negative consequences. For a long time, I was one of those people, until gradually, and then much more quickly and dramatically, I was not. My story is not particularly unique, but I share it with you in hopes that it might make a difference for you or someone you care about, and also to illuminate resources that are available to connect with others for help, even in the midst of a pandemic.

On September 14, 2007, exactly 5,000 days ago as I write this, I walked into a casino in Las Vegas and made what would prove to be my last bet to date, though I didn’t realize it at the time. Later that evening, my then-wife would confront me about a significant amount of hidden credit card debt in my name that she had discovered while doing an online credit check of our finances. At the time, I considered it the worst day of my life, but later I would begin to regard it as being the best day of my life. That day began a journey of personal self-discovery and recovery that has resulted in positive changes in nearly every area of my life.

That casino was where I went to gamble and also hide my gambling, as it was located only a few minutes from my daughter’s daycare facility. My wife would drop her off in the morning, and it was my responsibility to pick her up at the end of my workday. I knew that I could leave work a little early, gamble until just before the daycare closed at 6:30 pm, pick my daughter up, and arrive at home with no one the wiser.

I began gambling at a young age. After moving to Texas at the age of 10 to live with my father and his wife (my parents had been divorced since I was three), I recall our family vacations often taking the form of a 4-hour drive from Lubbock, Texas to Ruidoso, New Mexico where there is a horse racing track with pari mutuel wagering. We would camp in the mountains outside of town, which was great fun as a kid, though I’ve come to believe it was likely so that my father could save money on hotel costs so that he had more to gamble on the horses. We would drive into town during the day and spend the entire afternoon at the track. My father would give each of the kids $20 and that was ours to gamble. My father was the one placing the bets at the window, of course, but by the age of 10 I knew all the horse racing jargon, could read and understand the horses’ history and what the odds meant, and would tell my father how much to bet on which horse. I was “in action.”

When I was a teenager my father taught me how to play poker, and by the time I was in high school I was playing a weekly poker game with my father and a number of professors from Texas Tech University, where my father taught in the music department. It was my first “regular” exposure to gambling, and today it’s known that exposing children to gambling at a young age and the frequency of that exposure can create risk of a gambling problem later in life.

It was a friendly game, with nickel-dime-quarter limits, and no one winning or losing more than $15-20 in a session. It was a huge ego boost as an adolescent when I was allowed to play with men who were mostly three to four times my age, as well as a way to bond with my father. However, it was also my first exposure to some of the seedier stereotypes associated with gambling. My father would, on occasion, let me know that my stepmother “didn’t need to know that we’d been playing poker that day”—an indication that he was already experiencing a gambling problem himself that included lying to those important in his life and making his son complicit in those lies. On one occasion, I caught my father cheating during a poker game by looking at unexposed cards in the deck he was dealing from, while others were busy looking at the cards he had just dealt. I remember being incredibly shocked by the incident—not only by the simple fact that he was cheating, but especially because it meant he was cheating me as well—and I called him out on it at the table. I remember the stunned silence in the room, the admonition by one of the other players to “keep the cards on the table,” and the long, silent ride home…the final proof to me that what I had witnessed had actually happened, as there would have been some very strong words forthcoming from my father had I falsely accused him. We never spoke of it again.

As I began my college studies, also at Texas Tech, I became involved in a much higher-stakes poker game, when single hands could potentially yield hundreds of dollars. At that time, I still had control over my gambling. Simply said, I took only what I could afford to lose to the game, and if I lost my stake I left the game until I could afford to play again. Somewhat perversely, however, I won enough money in that poker game over the long run to move out of the house, get my own apartment, and quit my part-time job at Pizza Hut-—I had virtually no educational expenses, as I was studying under a full-ride scholarship at Texas Tech. I financed my entire life off that once-weekly poker game, not because I was a great player, but because there were two men in that game who were already suffering from a gambling problem, and who were inclined to stay in nearly every hand until the last card. I thought these two men (both very intelligent) were the world’s stupidest poker players, and I was happy to take their money along with everyone else in that game.

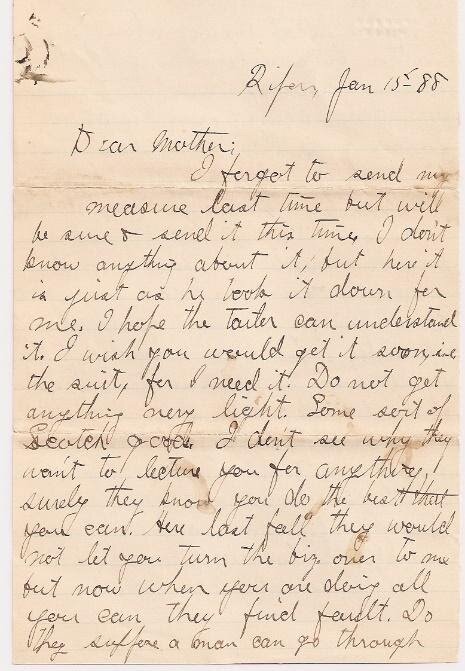

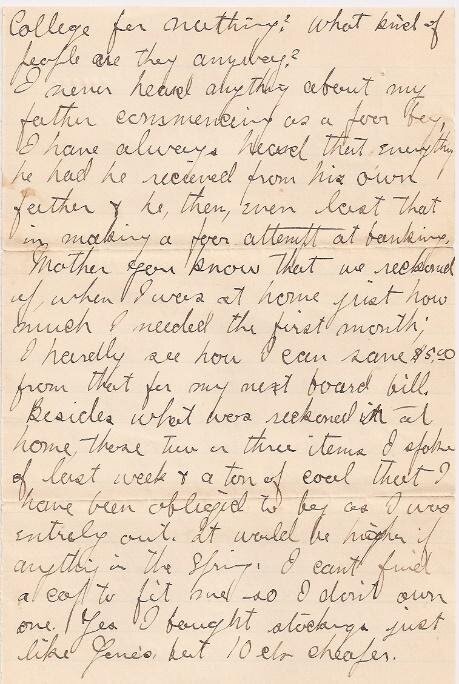

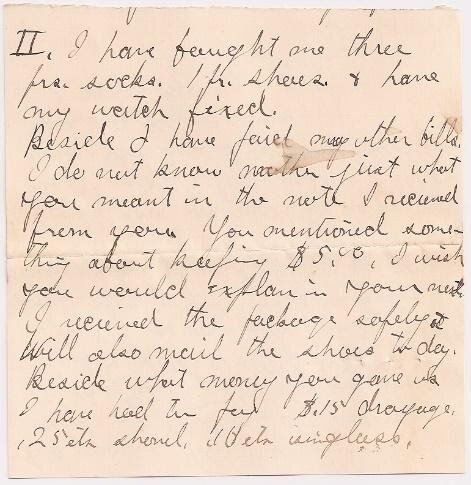

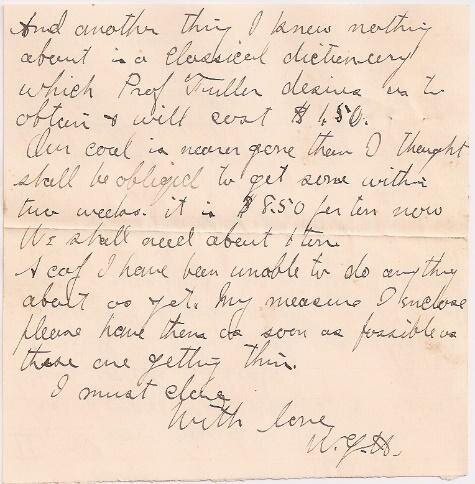

I’ve discovered that my life has been full of events that are known risks for the development of all kinds of addictive disorders. My family history of addiction on my father’s side likely goes back at least three generations—both cultural and genetic factors can influence generational transmission of the risk for addictive disorders. While my father’s gambling activities were clearly problematic, it was ultimately cancer caused by his nicotine use that ended his life a few years ago. According to my great aunt, his father “drank a little too much” sometimes, and her father (my great-grandfather) may have had a gambling or similar problem, based on 130-year-old letters he wrote home to his mother as a young man. Nearly every letter asks for money for many different reasons, and while that in itself isn’t proof positive anything extraordinary was going on, reading his words reminded me of all the times in the past when I would concoct stories to borrow money from my family, friends, or co-workers in order to get my “fix” at the casino without it showing up anywhere in the family finances.

Childhood trauma also conveys risk, and while I never suffered any physical trauma at the hands of my parents, I did witness a lot of psychological abuse and emotional manipulation by my father towards the two women he married after he and my mother divorced. I also experienced tremendous bullying in junior high and assault as a teenager, all of which undoubtedly provided fertile ground for some of the seeds that would later grow into and feed my gambling disorder.

When I landed a research faculty position at the Desert Research Institute (DRI) right out of graduate school in 1991, I was ecstatic. The big joke in my family had been, “If archaeology doesn’t work out for you, at least you’ve got your music to fall back on.” Both ended up working out surprisingly well for me—first the position at DRI, which I still have to this day, and later in 1999 when I became one of the founding musicians of the Las Vegas Philharmonic, an organization I still play for as a section cellist. But my big fantasy when I moved to Las Vegas revolved around saving enough money ($10,000) to enter the World Series of Poker and try to make it to that final table with Amarillo Slim, Doyle Brunson, and some of the other big names of the time. I did learn how to play poker in Las Vegas and even won the occasional small casino or company tournament. The day would come in 2007, however, when I would realize that I had lost enough money playing video poker, which became my primary gambling activity, to have entered the big game in the World Series of Poker every single year that I’d lived in Las Vegas,. Yet I never had entered…not even once.

Photos/Courtesy of Ted Hartwell.

It’s not something that happened overnight. I can look back now and recognize many of the signs that it was becoming a problem: suffering the onset of a voice disorder after moving to Las Vegas and using gambling as a way to isolate from the pain of being unable to sing or lecture; the unexpected loss of a relationship; some big wins in a short amount of time; slow but progressive loss of my ability to control limits. It’s easy to see all these things in hindsight, but at the time it was mostly just confusing.

Things reached a head (the first time) in 2005, and I promised my then-wife that I would no longer gamble. Over the next two years I twice went through a cycle of hiding debt and the fact that I was even gambling from her, and then coming clean. Each time I promised her I would stop, and each time I believed I would be able to stop. I remember attending my first 12-Step meeting in 2005 and hearing stories from people who had lost their families, who had embezzled money from their employers and spent time in prison. There were several who reported attempting to end their own lives, and many others who said they’d thought about it, mostly as a way to escape the pain of the mess they had created or to “save” their families from themselves. I found myself thinking I was glad that I wasn’t like the other people in that room (I would never do such things!), and I thought that simply hearing how bad it could get would be enough to keep me from gambling again, so I didn’t go back. I was wrong and inflicted a lot more damage on myself and my family over the next two years, until my own story was a lot closer in detail to some of those that I’d heard in that first meeting.

That night in 2007, when my wife confronted me about the hidden debt she had discovered, was also the night I identify today as the beginning of my recovery journey. The following day I had planned to send a check (ironically, for $10,000) to pay for a new cello that I had commissioned nearly seven years before. As part of the process of beginning to make amends to my family for the betrayal and financial impact I had caused them, I agreed not to buy the cello and enrolled in an intensive outpatient program to treat my gambling disorder. That little girl who was once my cover for helping me hide my gambling is now firmly where she belongs in my life…as the daughter of a caring and devoted father.

Today, nearly 14 years later, I serve as a consultant for community engagement to the Nevada Council on Problem Gambling and the local gaming industry, and I am proud to have served the State of Nevada on the Advisory Committee on Problem Gambling since 2012 at the pleasure of three different Governors of Nevada. Before the pandemic (and hopefully again soon) I spoke to kids in Nevada schools about gambling and video game awareness and also to high school student athletes that hope to play at the collegiate level about the potential risks of certain types of gambling to their athletic and educational careers. As we begin the process of recovery from the pandemic, I see parallels with so many of the things I experienced in my life and the numerous impacts that so many have suffered, compressed into a relatively short time, heightening the risks of both gambling and substance use disorders moving forward. Know that, even as restrictions necessitated by the pandemic begin to lift and the music begins to return, there are many resources available both in-person and online to assist those struggling with this often hidden illness. My life is very good today because I took advantage of those resources then, and even if you or a loved one are struggling now, it can be for you too!

Gambling disorder is a very real and potentially deadly illness, but also very treatable, with significantly positive treatment outcomes. For more information, and to connect with resources, visit:

Nevada Council on Problem Gambling

Gamblers Anonymous of Southern Nevada

Online Meetings for Gamblers, Family and Friends in Recovery

Recovery Road Online – Help for Problem Gamblers

National Council on Problem Gambling

For immediate assistance, please call the Problem Gamblers Help Line at 1-800-522-4700.

Photo/Brent Holmes.

William “Ted” Hartwell has an M.A. in Anthropology from Texas Tech University and has been a member of the research faculty of the Desert Research Institute (DRI) in Las Vegas since 1991. Mr. Hartwell is the Project Director for DRI’s Community Environmental Monitoring Program, which provides a hands-on role for members of the public in the operation of a network of radiation and weather monitoring stations located in communities surrounding and downwind of the Nevada National Security Site (NNSS), formerly known as the Nevada Test Site.

Previously, Mr. Hartwell’s archaeological research focused on three geographic regions: the southern Great Basin, the southern Great Plains, and the pampas of Argentina. Specific interests have included hunter-gatherer lithic technology, caching behavior, quarrying behavior, and soil formation processes. His research has included investigations of a historic toll road in north-central Nevada, an examination of quarrying behavior in the southern Great Basin, late Paleoindian lithic technology on the Plains, and participation in a study comparing and contrasting human adaptation on the U.S. southern Great Plains and Argentinean pampas. He also has produced a publication for the public that discusses archaeological research at Yucca Mountain on the NNSS.

He is the Principal Investigator of a research study examining the impact of problem gambling in Native American tribal communities in Nevada. As a problem gambler in long-term recovery, he promotes awareness, prevention, and treatment of problem gambling as the Community Engagement Liaison for the Nevada Council on Problem Gambling. He has served at the pleasure of multiple Nevada Governors on the State Advisory Committee on Problem Gambling since 2012. He was the 2014 Shannon L. Bybee Award recipient for his continuing work on advocacy, outreach, and research on the issue of problem gambling.

Mr. Hartwell lives in Las Vegas, where he is also a professional cellist with the Las Vegas Philharmonic, a devoted husband to a recent Russian immigrant, and the proud father of a precocious 15-year-old daughter and three cats.

Thank you for visiting Humanities Heart to Heart, a program of Nevada Humanities. Any views or opinions represented in posts or content on the Humanities Heart to Heart webpage are personal and belong solely to the author or contributor and do not represent those of Nevada Humanities, its staff, or any donor, partner, or affiliated organization, unless explicitly stated. At no time are these posts understood to promote particular political, religious, or ideological points of view; advocate for a particular program or social or political action; or support specific public policies or legislation on behalf of Nevada Humanities, its staff, any donor, partner, or affiliated organization. Omissions, errors, or mistakes are entirely unintentional. Nevada Humanities makes no representations as to the accuracy or completeness of any information on these posts or found by following any link embedded in these posts. Nevada Humanities reserves the right to alter, update, or remove content on the Humanities Heart to Heart webpage at any time.